Dr. Dougall’s article contains definitions, concepts, tips and insights on what research teaches us about issues management. As the paper explores selected concepts from contemporary business and communication scholars, readers are encouraged to post comments and to click on the links to the author’s original sources.

Issues management is a seductive concept. For those who are talented and tenacious enough to make their careers in public relations, the idea of “managing” contentious issues–taming them, bringing them to heel and making them do our bidding–is illusory, but utterly compelling. For those who have battled for the legitimacy of public relations as a management function, the credibility and senior management access issues management can deliver is something that communication professionals may find only in the midst of crises. A 2007 survey of CEOs revealed their expectation that communications chiefs be equipped to “see around corners” and anticipate how different audiences will react to different events, messages and channels (The Authentic Enterprise, 2007, p. 44).

Issues management is all about facilitating communication leadership in organizations. In fact, the USC Annenberg 2007 GAP V survey of senior public relations practitioners revealed that those with direct budgetary responsibility for issues management (42 percent) were more likely to report higher levels of C-suite support, effective working relationships with other departments, larger budgets, and more access to resources for research, evaluation and strategic implementation. So emphatic was the relationship between issues management and key indicators of effective practice, the authors added establishing an issues management strategy to the list of 13 best practices for public relations.

This journey begins in Module 1 with important definitions, concepts, tips and insights for those looking for an overview of discipline. Module 2 provides a brief overview of the origins of the discipline and Module 3 explores selected concepts from contemporary scholars of business and communication strategy.

Module 1–The Practice of Issues Management

Issues management defined

Issues management is an anticipatory, strategic management process that helps organizations detect and respond appropriately to emerging trends or changes in the socio-political environment. These trends or changes may then crystallize into an “issue,” which is a situation that evokes the attention and concern of influential organizational publics and stakeholders. At its best, issues management is stewardship for building, maintaining and repairing relationships with stakeholders and stakeseekers (Heath, 2002).

Organizations engage in issues management if decision-makers are actively looking for, anticipating, and responding to shifting stakeholder expectations and perceptions likely to have important consequences for the organization. Such responses may be operational and immediately visible, such as McDonald’s anticipatory move from plastic to paper packaging in 1990. Other common strategic responses are direct, behind-the-scenes negotiations with lawmakers and bureaucrats, and proactive campaigns using paid and earned media to influence how issues are framed. Pro-life (e.g. National Right to Life) and pro-choice organizations (e.g. Planned Parenthood) are well-established institutions that have long contended the same issue using many similar strategies and tactics, but with opposing and openly antagonistic positions.

Issues should precipitate action when a collective, informed assessment demonstrates that the organization is likely to be affected. For example, in 2007, changes to local laws made the retrofitting of car sunroofs illegal in Beijing and left a national manufacturer of sunroofs scrambling to negotiate with other local and regional governments to protect their profitable business. Introduced in advance of the 2008 Olympics, the laws were the outcome of lobbying by various stakeholders, including health and safety agencies, and car manufacturers. The emerging trend was increased attention being paid to health and safety concerns in that city–including air quality, motor vehicle safety and traffic reduction. The sunroof manufacturer was caught in the crossfire of stakeholder interests, unable to respond effectively. The outcome was substantive and negative.

In contrast, the America West Arena in Phoenix, Arizona, provided an example of effective issues management in action when it worked with disabilities advocacy groups to ensure a new arena would not merely comply with the specifications of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), but rather, would meet a higher standard set collaboratively (Matera & Artique, 2000). Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE or “mad cow disease”) had been on the issues management radar of the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association (NCBA) for years when, in 2003, the first case of BSE on American soil was identified in Washington State. By anticipating the event and mapping out a goal-driven response in advance, the NCBA was able to respond rapidly. Helped by the fact that only one infected animal imported from Canada had been identified, the following strategic response effectively contained consumer concerns about American beef. The response was multi-layered, including direct consultation with regulators, consumer advocacy groups and other key stakeholders, as well as intensive national and international news media outreach. Evaluation measures, such as media coverage achieved, were positive. More significantly, beef demand rose by almost 8 percent in 2004 and consumer confidence in American beef increased from 88 percent just prior to the BSE event in 2003 to 93 percent in 2005; consumer spending on beef also increased an estimated $8 billion between 2003 and 2004 (National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, 2005).

So, who should practice issues management? Chase (1984) argued that issues management is a natural fit for public relations and its various disciplines including public affairs, communications and government relations. Heath and Cousino (1990) argued that public relations practitioners understand and can play important roles in increasingly complex environments, including promoting the bottom line interests of the organization and building relationships. Issue communication is an important strategic component of issues management, but good decisions about communication strategies and tactics are more likely to be made by practitioners who understand the full scope of issues management, have an extensive knowledge of the organization and its environment, and are skilled collaborators equipped to negotiate within and across organizational boundaries.

A 2002 survey by the Foundation for Public Affairs revealed that 44 percent of all companies with an internally recognized public affairs function have staff members working on issues management full-time. The same survey showed that within companies regularly using non-dedicated members to manage issues, 71 percent obtain these individuals from other corporate staff functions like human resources or finance (Mahon, Heugens & Lamertz, 2004). Furthermore, Regester and Larkin (2005) contend that public relations practitioners “are well placed to help manage issues effectively, but often lack the necessary access to strategic planning functions or an appropriate networking environment which encourages informal as well as formal contact and reporting,” (p. 44). Clearly, issues management is a process that demands cross-functional teams and effective collaboration.

Issues

In the context of corporate issues management, issues are controversial inconsistencies caused by gaps between the expectations of corporations and those of their publics. These gaps lead to a contestable point of difference, the resolution of which can have important consequences for an organization (Heath, 1997; Wartick & Mahon, 1994). While organizations, stakeholders and other constituencies may be concerned about the same issue, their perspectives are rarely the same. The role of the issues management process is to divine and determine the existence and likely impacts of these contestable points of difference. See the Issue Management Council’s clarification for more information on the subject.

Issues development

Issues are commonly described as having a lifecycle comprising five stages–early, emerging, current, crisis and dormant. In simple terms, as the issue moves through the first four stages, it attracts more attention and becomes less manageable from the organization’s point of view. In other words, if the organization’s issues management process detects an issue in the earliest stage, more response choices–such as product modification, the introduction of new conduct codes or anticipatory collaboration with key interest groups–are available to decision-makers. As the issue matures, the number of engaged stakeholders, publics and other influencers expands, positions on the issue become more entrenched and the strategic choices available to the organization shrink. If and when the issue becomes a crisis for the organization, the only available responses are reactive and are sometimes imposed by external parties, such as government agencies. Not all issues reach the crisis stage and many crises are not the result of an underlying issue.

For example, an ice storm in November 2002 caused extensive, multi-day power outages in North and South Carolina. In spite of steps taken by the health authorities and major power utilities to issue standard warnings about the indoor use of generators, gas grills and charcoal grills for temporary heating and cooking, hundreds of carbon monoxide poisoning cases were recorded across the state during the power outages that followed. Disproportionately represented among the affected were non-English speaking Latino immigrants. The warnings, issued only in English, had failed to reach the rapidly expanding migrant, Spanish-speaking labor force moving into North Carolina. The utilities and many other corporate and government organizations in the state had neglected to recognize the many implications of a growing population of non-English speakers. Although not culpable for the deaths, the utilities recognized the need to transform their capacities to communicate effectively across language barriers in emergencies. The issue was not the ice storm or the power failure, but the fact that experienced and well-resourced utilities with sophisticated communications departments and carefully crafted public profiles failed to anticipate the changing state demographics and to incorporate known variables, such as the increasing number of energy consumers without English literacy. There was a gap between the performance stakeholders–regulators, special interest groups and citizens–expected of these companies and their actual performance.

Essential steps in issues management…

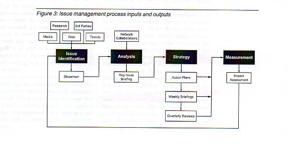

Heath (1997) argues that issues management is the proactive application of four strategic options: (1) strategic business planning, (2) getting the house in order–corporate responsibility, (3) scouting the terrain–scanning, identification, monitoring, analysis and priority setting, and (4) strong defense and smart offence–issues communication. Developed by and for practitioners, Palese and Crane (2002) propose a four-stage model comprising issue identification, analysis, strategy and measurement (see Figure 1). Regester and Larkin (2005) recommend a seven-step process including monitoring, identification, prioritization, analysis, strategy decision, implementation and evaluation (see Figure 2).

While there are many models of the issues management, most contend that the process comprises between five and 10 steps that fall into three major categories: (1) issue identification and analysis, (2) strategic decision-making and action, and (3) evaluation. Practitioners and scholars alike have tended to focus most on the first two categories of steps (See Anticipatory Management Process).

Steps in issue identification and analysis include scanning and monitoring. At the strategic decision-making stage, an appointed issue action team analyzes the issues and priorities in more detail. This team should include people who are closest to the issue and best equipped to direct and implement the organization’s response. At this stage, the team allocates resources to an emerging or current issue and initiates the investigation of various strategic options–including issue communication. Finally, the decisions enacted are evaluated. The process requires ongoing collaboration of key internal stakeholders, facilitated by frequent interaction. In other words, issues management demands cross-organizational collaboration, regular teleconferences and email communication, and face-to-face meetings. Issues managers don’t just plug into a database and relinquish all responsibility to information science.

Issue Identification

Scanning–The first step in effective issues management is the application of informal and formal research methods to explore the organization’s environment. The assumption is that mindful scanning of the environment is a kind of insurance against “surprise threats or missed opportunities” (Bridges & Nelson, 2000, p. 112). While the labels applied may vary, organizational environments are typically divided into sectors, including the social (i.e. public opinion/reputation), economic, political/regulatory and competitive.

Given our information-rich time, the challenge is not sourcing information, but in mining that information for organization-relevant, intelligible and credible insight. In general terms, environmental scanning is the systematic, multi-method collection and review of potentially relevant data from industry, government and academic sources. Long laundry lists itemizing where to scan for early and emerging issues are provided in essential texts such as Robert Heath’s “Strategic Issues Management.” These lists change over time as information and communication technologies expand and improve.

Monitoring–While often paired with scanning and used interchangeably, monitoring is conceptually and practically a step separate from scanning. When scanning systems reveal a situation or problem with the earmarks of an emerging organizational issue, the decision to monitor should be taken. Heath (1997) argued that monitoring should occur only after the issue meets three criteria: The issue (1) is listed in standard indexes, which suggests growing legitimacy as signaled by journalists and other opinion leaders, (2) offers a quantifiable threat or opportunity in terms of the organization’s markets or operations, (3) is championed by a group or institution with actual or potential influence.

Strategic Decision-making

Prioritization–Determining which issues demand organizational response and, therefore, the allocation of resources demands detailed analysis. Although there are many ways to analyze issues using open access and proprietary models, the two most critical dimensions of issues are probability of occurrence and organizational impact. In other words, (1) How likely is the issue to affect the organization? and (2) How much impact will the issue have? No two issues are equal and should not be treated as such. Issues can be moved up on the agenda for action, or back to continued monitoring, depending on prioritization. Managers assigned by organizations to monitor issues should define and prioritize their publics based on the opinions people hold and their degree of involvement with the issues (Berkowitz & Turnmire, 1994; Vasquez, 1994). Issues that spread rapidly through the Internet–issue contagions–present a relatively new and volatile challenge that is particularly important at the prioritization stage (Coombs, 2002). In other words, assessing the likelihood of an issue gaining momentum via the Internet must be considered.

Strategic Options–Like any other management discipline, robust issues management strategy emerges from sound data, diverse viewpoints and ingenuity. Assembling the right people, sometimes called an issue action team,arming them with credible information, and identifying realistic and measurable objectives provides the foundation for effective anticipatory and responsive strategy development. Anticipatory management specialists William Ashley and James Morrison contend that scenarios are a highly effective way to stimulate strategic thinking by helping provide maps of the alternate pathways along which issues may develop. Ashley and Morrison suggest a six-step approach to creating multiple scenarios, specifically:

- Frame an issue (For example, how is the organization contributing to environmental degradation of the area and what can be done to reduce the negative impact?);

- Specify decisions factors (What questions must be addressed?);

- Identify environmental forces by scanning and monitoring; select a logic or story line (Explain why and how these forces might take different paths. For example, energy utilities faced with environmental concerns are making choices between “retro-fitting” or updating existing facilities vs. rebuilding and repowering new facilities );

- Develop alternate scenarios (For example, “short-term, low-cost and higher risk of failure,” or “medium-term, higher cost and more permanent”);

- Decide implications and recommend actions.

Action Taking–According to issues manager practitioner-expert Tony Jacques, the greatest barriers to effective issues management are the lack of clear objectives, and unwillingness or inability to act (Jacques, 2000). As Jacques points out, issues management is a process with achieved results. The scanning, monitoring, prioritization and strategic decision-making steps have no value unless action is taken toward achieving specific and measurable objectives. Jacques also makes the point that issues management no longer “belongs” to corporations; in fact, community organizations, NGOs, and other activist and advocacy groups have enacted some of the most innovative, aggressive and successful issue management initiatives of the modern era. See, for example, Greenpeace’s role in drafting the Kyoto protocol in 1997, an international treaty to curb greenhouse gases. The agreement was subsequently ratified by almost all countries other than the United States. One essential ingredient for success of initiatives like this is that they are guided by singularly clear objectives set and driven by committed actors who are willing and able to take action.

Evaluation/Measuring Outcomes

The steps involved in evaluating the success of issues management initiatives will vary as much as the issues themselves. The first and most crucial step in evaluation is setting clear and measurable objectives. Mark Twain’s maxim “If you don’t know where you’re going, any road will get you there,” is as applicable to issues management as it is to any other endeavor.

Practitioners today have access to more measurement tools than ever before; the challenge is to find the tools that best fit the set objectives. For example, measuring the extent and tone of media coverage is meaningful only if one of the pursued objectives is to secure specific media attention in t erms of volume, channels, tone and so on. Other objectives, such as influencing the drafting of legislation, positioning the organization effectively in relation to an industry-wide problem, or correcting allegations about a product or service all require different metrics. While the drafting of legislation can be tracked relatively easily, repositioning or correcting allegations present more complex measurement challenges and require insights into the identity, perceptions and behaviors of target stakeholders before and after the issues strategies are enacted. Tools such as surveys and interviews, as well as behavioral measures such as purchasing decisions, may all be necessary to evaluate such a layered objective. More resources than ever before are available to guide practitioners through their measurement and evaluation challenges, which are comparable across disciplines rather than specific to any one process. See, for example, Using Public Relations Research to Drive Business Results by Katharine Delahaye Paine, Pauline Draper and Angela Jeffrey.

Figure 1. Palese, M. & Crane, T.Y. (2002). Building an integrated issue management process as a source of sustainable competitive advantage. Journal of Public Affairs, 2(4), 288.

Figure 2. Regester, M. & Larkin, J. (2005). Risk issues and crisis management: A casebook of best practice. (pp. 125-126). London; Sterling, VA: Kogan Page.

Step 1–Monitoring

- Analyze the business environment.

- Scan and monitor what is being said, written and done by public, media, interest groups, government and other opinion leaders.

- Consider what may impact on the company or its divisions.

Step 2–Identification

- Assess from the business environment those elements that are important

- Look for a new pattern emerging from what most people take for granted.

- Identify the issue that impact on the company and are gaining widespread support.

- What is the type of issue and where is it in its lifecycle?

Step 3–Prioritization

- How far-reaching will an issue’s impact be (product sector, company, industry)?

- Assess what is at stake—Profit? Reputation? Freedom of action?

- What is the probability of occurrence?

- How immediate is the issue?

Step 4–Analysis

- Analyze the most important issues in some detail.

- Determine their probable impact on the company or its divisions as precisely as possible.

- Establish issue support teams if appropriate.

- Identify/rank stakeholders.

Step 5–Strategy decision

- Create a strategic response and define the content of the message.

- Identify the target groups.

- What are the company’s strategic options?

- What resources are needed?

- What specific actions should be taken? By whom? When? With whom?

- Develop issue management communication plan and consider timing.

Step 6–Implementation

- Implement the policies and programs approved by management.

- Communicate the response effectively with each target group in a credible form.

- Advocate the company position to prevent negative impacts and encourage actions with beneficial effects.

Step 7–Evaluation

- Assess results.

- Evaluate the success of policies and programs to determine future strategies.

- Capture lessons from failures and successes.

Best practice tips and trends

Organizations must account for an ever-expanding range of issues–trans-fatty acids, the environment, genetic modification, money laundering–and their leaders are “obligated to position themselves in debates surrounding social consequences over which they have little of no direct control” (Scott & Walsham, 2005, p. 308). While the need for effective issues management is more acute than ever, the Issue Management Council has identified nine best practice indictors. Led by Tony Jacques, the outcomes of the ambitious Issue Management Council Best Practice Project are detailed in his article Using Best Practice Indicators to Benchmark Issue Management,(Public Relations Quarterly, Summer 2005). These best practice indicators are organized into three categories–structural, implementation and integration. A brief summary follows:

Structural indicators

- There is an established mechanism to identify current and future issues through environmental scanning and issue analysis.

- The organization has adopted a formal process to assign and manage issues.

- Responsibility for stewardship of the issue management process is clearly assigned and mechanisms are in place to build organizational expertise in the discipline.

Implementation indicators

- Ownership of each major issue is clearly assigned at an operational level with accountability and results linked to performance reviews.

- Progress against key issues is formally reviewed with organizational owners on a regular basis and the status of each is monitored at the highest management level.

- The executive committee/board has fiduciary oversight of issue management; has mechanisms in place to report progress to directors and/or external stakeholders; and has authority to intervene in the event of non-compliance or misalignment.

Integration indicators

- Formal channels exist for managers at all levels to identify and elevate potential issues for possible integration into broader strategic planning, including external stakeholder management.

- Management of current and future issues is well-embedded within the strategic planning and implementation processes of organizational clients/owners.

- Issue management is recognized and organizationally positioned as a core management function that is not confined to a single function or department.

For a practical description of a corporation engaged in issues management, Palese and Crane (2002) offer a detailed case study from DaimlerChrysler. This company is committed to “a weekly process that uses several innovative tools to stimulate collaborative dialogue with a team of global managers who are all, technically, issue managers,” (p. 285). In brief, the process is as follows. (1) Monday–issue identification and analysis involving issue process stewards and issue managers collaboratively explore intelligence (2) Monday/Tuesday–An issue strawman is produced and circulated. This is a document proposing the issues most relevant at that time. After being circulated globally to 175 people within DaimlerChrysler, the proposal is discussed via email and conference calls. (3) Tuesday/Wednesday–After these discussions, a key issue briefing is developed. This briefing includes actionable intelligence, and provides the name and contact information for the lead issue manager (p. 287). (4) Wednesday/Thursday–The draft is in review by senior management and, on (5) Friday, the briefing is distributed to the Board of Directors and other senior personnel. See resources listed at Issue Action Publications for more on this, and other prescriptive models and recommendations.

Key Issues Management Insights

Most definitions of issues management are organized around the core idea that it’s a strategic planning process used to detect, explore and close gaps between the actions of an organization–specifically a corporation–and the expectations of its stakeholders (Heath, 1997). Emerging in the 1960s as an organizational response to uncertain socio-political environments, issues management was originally described only in defensive terms as an early warning system or process that helps organizations avoid undesirable public policy outcomes. By the 1990s, practitioners and scholars began to give explicit recognition to the critical role of stakeholder expectations, but the emphasis continued to be on the reactive and defensive role played by issue managers in relation to “closing gaps” and avoiding problems. Today, issues management is applied both opportunistically and offensively, progressing from reactive crisis prevention tool to maturing strategic management discipline (Jacques, 2002). Furthermore, contemporary issues management can be much more than a defensive process useful only to corporations. The shared concerns of stakeholders and other interested publics–advocacy organizations, non-government organizations, government departments and agencies, the news media and opinion leaders–bring issues to life and keep them on the public agenda. The strategies and tactics of issues management have long been a tool of organized labor, government and even activists, not only corporations (Heath, 2006). No discussion of issues management would therefore be complete without giving explicit recognition to the influence of organizations and groups outside the corporate realm.

While strategic planning is concerned with the organization’s plans for itself, issues management is concerned with “the ‘plans’ the sociopolitical environment–the public policy process–would make for the institution” (Ewing, 1980, p. 14). As a practice, issues management demands research expertise (data gathering, analysis and interpretation), mindfulness, a rich and current understanding of the socio-political environment of the organization, the industry and perhaps most importantly, the ability to advocate with senior management and across organizational boundaries. One person is unlikely to possess all these attributes, but these are the resources that must be marshaled in the issues management process. In sum, issues management is a complex discipline worthy of further scrutiny, keeping the following provisos in mind.

Process, not a promise

A well-designed issues management process that has authentic management support can help move the organization closer to its goals, empowering managers to anticipate and respond to changes in its external environment. Many observe that issues management is a misnomer because the term overstates the capacity of any organization to control issues that have emerged in public opinion, public policy and other dimensions of the socio-political environment. “Certainly, no corporate staff function can manage a public issue to a corporation’s desired conclusion with any regularity” (Arrington & Sawaya, 1984, p. 148).

Explicitly research-based

Most definitions of issues management will specify steps and stages in the process, including (1) environmental scanning, (2) issue identification, (2) issue impact assessment and prioritization, (3) development of objective-driven strategy, (4) action and (5) evaluation. Identifying an issue and figuring out if and how much it’s likely to matter to an organization now and in the future demands insight that can only emerge from formal and informal research.

Not just for corporations

Don’t be deceived. You don’t have to be a corporate communication or public affairs specialist to be engaged in issues management. Issues management is relevant to organizations, activists and advocacy groups. Any organization or group formally or informally engaged in pursuing an issue that is relevant to its goals can benefit from understanding issues management concepts and processes. Indeed, the discipline has much to gain from the attention and contributions of practitioners and scholars with diverse interests beyond business goals and corporate concerns.

Issues concern everyone

While public relations and public affairs practitioners and scholars have driven much of the discussion about and development of issues management over the past 40 years or more, issues management does not belong exclusively to just one or two departments and is not a line function. It is a process to organize an organization’s “expertise and enable it to participate effectively in the shaping and resolution of public issues that critically impinge upon its operations” (Arrington & Sawaya, 1984, p. 148). More specifically, the charge on any given issue should be led by “the person with the greatest personal and financial accountability for the Issue (sic); the most to lose if it goes bad; and the capability to make decisions and commit resources” (Jacques, 2000, p. 49).

Communication is one strategic option…

But, don’t focus on communication at the expense of understanding the critical importance of other functions. Communication specialists who are blind to operational opportunities and constraints, and to the wider strategic goals and processes of an organization, cannot fulfill the boundary-spanning demands of any contemporary communication management role. That includes the role of issues manager.

Collecting data is easier than ever, but what does it mean?

Like so much of what compels the attention of public relations practitioners and scholars, issues management is easy to define, makes intuitive sense and is worthy of being labeled a critical organizational function. Measuring and evaluating the success or failure of issues management in practice, however, is conceptually and practically complicated. Articulating measurable objectives at the outset of any issues management initiative is an essential first step.

Issues management is not the less glamorous precursor to crisis management

While one of the benefits of effectively responding to emerging issues may be the successful aversion of a future crisis, to frame issues management only in terms of what it helps organizations to avoid is inaccurate and very limiting. Issues management is about moving the organization forward by offensively addressing strategic goals. While one of the side-benefits may be the aversion of crises, it’s a mistake to characterize the discipline as defensive and reactive (Heath, 1997, 2006; Jacques, 2002). In fact, competitive advantage depends as much on the organization’s ability to respond effectively to non-market forces–including issues, activists, stakeholders, public policy and public opinion–as its ability to satisfy the marketplace (Mahon, Heugens & Lamertz, 2004).

Risks and Issues are not the same

Risks and issues are not interchangeable concepts. The application of issues management and risk management processes may, however, overlap when issues emerge in the issue environment that result from contention over the risks associated with an organization such as a product, service, policy, by-product or some other aspect of its operations. A case-in-point is the debate about the effective communication of risks associated with prescription drugs. The United States pharmaceutical industry is widely criticized for inadequately communicating the risks of many popular and widely advertised drugs. The risks and communication of those risks have precipitated the widespread attention of the public, media, advocacy groups and regulators. The issue that compels the concern of stakeholders and publics* is about the drug companies’ perceived willingness to put profits before people. Their failure to adequately communicate risk is a dimension of that issue.

Useful resources

Public Affairs Council

http://pac.org/

Issue Action Publications

http://www.issueactionpublications.com/documents/products.htm

Issue communication:

For detailed discussions, see Strategic Issues Management, by Robert Heath (1997, 2008; Sage), and

Today’s Public Relations: An Introduction by Robert Heath & W. Timothy Coombs (2006, Sage).

USC Annenberg Strategic Public Relations Center Public Relations—Generally Accepted Practices Study

(GAP IV): http://annenberg.usc.edu/CentersandPrograms/ResearchCenters/SPRC/PrevGAP.aspx.

Includes information on such topics as budgets for public relations departments within corporations, as well as staffing levels, reporting lines, and the use of outside public relations firms.

For critical views of corporate issues management activities and related topics, see Corporate Watch, PR Watch and Greenpeace.

See the complete bibliography and list of references for more resources.

Module 2 – The Origins of Issues Management

Modern approaches to issues management emerged in the 1960s, a time of significant social change. Public disaffection with business began to manifest in regulations and other public policy initiatives. Today, the Public Affairs Council describes issues management as “the process of prioritizing and proactively addressing public policy and reputation issues that can affect an organization’s success.” The addition of the word “reputation” is an important one that pushes the discipline beyond the public policy boundaries of earlier models of issues management. Many large companies, in particular, use issues management techniques “to keep all of their external relations activities focused on high-priority challenges and opportunities” (Public Affairs Council, 2008).

Issues management developed to address the problem of actual and potential government intervention in business. Managers at private corporations could systematically scan for emerging “problems,” in their view, to exert influence and control in relation to the direction of public policy. H. Igor Ansoff, the preeminent strategic management scholar, argued that the primary objective of issues management was to provide corporations with an early warning system designed to detect weak signals that might precede potentially harmful social trends before they matured (Ansoff, 1975).

A prominent voice in the early years of the discipline, W. Howard Chase defined issues management as “the capacity to understand, mobilize, coordinate, and direct all strategic and policy planning functions and all public affairs/public relations skills, toward the achievement of one objective: meaningful participation in creation of public policy that affects personal and institutional destiny” (Chase, 1982, pp. 1-2). Elaborating this description with a military metaphor, issues management strategy “…anticipates and attempts to shape the direction of public policy decisions by determining the theater of war, the weapons to be used, and the timing of the battle itself” (p. 59). Chase’s perspective was explicitly and unapologetically pro-business, antigovernment and asymmetrical (Grunig & Repper, 1992).

Underpinning the search for clues and signals of danger ahead was the rationale that when an organization “fails to respond to the public issues process ‘voluntarily,’ federal or state regulations can and, in most cases, will eventually force a response acceptable to the general public” (Renfro, 1993, p. 27). Tucker, Broom & Caywood (1993) defined issues management as a process that benefits both the organization and its primary shareholders by helping to preserve markets, reduce risk, create opportunities and manage image as an organizational asset. In contrast, Graham Knight’s pro-social perspective contends that because issues management developed out of the long-established business practice of lobbying governments with respect to fiscal, legislative and regulatory intervention, issues management is all about “influencing, if not controlling, government intervention in a way that preserves and enhances corporate interests and autonomy,” (2007, p. 313).

The corporate public affairs function, from which issues management initiatives emerged, was most often created as a firm’s response to crises (Griffin, 2005). Working with limited resources in difficult environments and often reporting directly to the CEO, “public affairs executives worked with governmental legislators and regulators, and created strategies often reflecting a late stage, resistance/reactive, or ‘firefighting’ mode.” (p. 466). By the time public affairs executives stepped into the debate, the public policy issue was generally far along the issue life cycle (Mahon, 1989). Efforts to define the scope and responsibility of issues management in a proactive rather than reactive mode first emerged in the 1990s (Heath, p. 210).

Module 3 – More about Issues and Issues Management

If you are interested in enriching your understanding of issues management by exploring further concepts and challenges, read on!

Models of Issues Management

Crable and Vibbert (1985) developed the catalytic model of issues management, which divides issues management into five stages–potential, imminent, current, critical and dormant. In the potential stage, an individual or group recognizes a problematic situation. In the imminent stage, other people or groups see the value and/or legitimacy of the issue and get involved. The current stage describes the point at which the issues is known by a large number of stakeholders and is typically the point at which widespread media attention is engaged. Decisions are made and action taken at the critical stage. The issue is considered dormant when it has been resolved (Coombs, 2002).

Palese and Crane (2002) contend that there are four evolutionary issue management models representing a continuum from least to most evolved–observational, communicative, coordinated and integrated. The observational model casts issue management as a data-tracking or research function. In the communicative model, issue managers are close to key audiences like “plant managers, field sales reps, subject matter experts or relationship managers who deal every day with issues in their areas of expertise” (p. 289). The observational and communicative models are “the least sophisticated and strategic and the most common” (p. 289). The coordinated model introduces the issue process steward. The steward’s job is to “nurture and develop the issue management process, stimulate dialogue among issue managers and key constituencies, and most importantly, to continually reinvent the process of ‘connecting the dots’, on an enterprise-wide scale, based on the intelligence provided by issue managers and many other sources” (p. 289). The rarest and most sophisticated of models is the integrated issue model in which senior management “…play an informed and active role in understanding issues. They are eloquent communicators, but ensure that actions and policies of their company are aligned with practice and performance” (p. 290).

Prominent issue management expert Tony Jacques, a public affairs veteran in the chemical industry, argues that the increasing focus on tailored models by practitioners and scholars is helpful, but not without negative consequences. In addition to that, the increased and more serious attention to measurement and evaluation has precipitated a modeling and measurement mania, diverting the attention of both practitioners and scholars from the critical question of which are most likely to deliver the most positive outcomes (Jacques, 2005).

Issues are not objects

Jones and Chase (1979) described issues as questions precipitated by changes in the environment that are waiting for decisions. J.K. Brown (1979) defined issues as conditions or pressure points, internal or external to the organization, likely to significantly affect an organization. Crable and Vibbert contend that issues are created when one or more human agents attach significance to a situation or perceived problem (1985). In this vein, Smith (1996) rejected the perspective that issues are objects waiting to be discovered by organizations. Instead, he argued for a more explicit focus on the role of human attention and interest in creating and sustaining issues. Issues appear as groups of people organize and demand their concerns be addressed (Grunig & Repper, 1992). The recognition and engagement of interested groups of people is what sustains issues and makes them legitimate sources of concern and response for organizations.

Wartick and Mahon (1994) argued that issues are fundamentally controversial inconsistencies caused by gaps between the expectations of corporations and that of their publics. Business strategy scholars Ashley and Morrison define an issue as “an internal or external development that could affect the organization’s performance. The issue is one to which the organization must respond in an orderly fashion and over which it may reasonably expect to exert influence” (1995, p. 123).

Another perspective on issues versus problems

Defining issues using the benign-sounding and value-free terminology of “expectation gaps” is not acceptable to everyone. Graham Knight argues that transforming a problem into an issue is “to play down its problematic character while acknowledging that there is something–a topic or question–that needs to be addressed, especially discursively” (2007, p. 313). In this conceptualization, issues are not expectation gaps, but rather “problems that have been neutralized to some extent,” which, Knight argues, makes them matters of common interest and concern, amenable to negotiation and reform (p. 313). Contending that the language of issues has stronger connotations of consensus than the language of problems, “the effect of this is to depoliticize the focus of contention to some extent. Issues imply relations of difference rather than antagonism,” (Knight, p. 313). Similarly, Regester and Larkin argue that activists “deal with problems; companies tend to deal with issues, and there is a difference,” (2005, p. 15). From this perspective, a problem is bigger and more encompassing–pollution, labor exploitation, discrimination, poverty–while an issue is more contained and specific, involving “potential solutions–regulation to curb emissions; codes of practice to improve workers’ rights…” (p. 14).

Issues and the media

Organizations, activists and other issue stakeholders may seek media attention to advance their goals, or the attention of the media may be an unwelcome, but unavoidable, side effect of the conflict. Either way, the higher the degree of obvious conflict in organization-activist relationships, the more likely that media attention and coverage will result (L.A. Grunig, 1992; Heath, 1997; Olien et al., 1989). Increased media coverage is more likely to occur when the organization is failing to meet stakeholder expectations (negative expectational gaps). If the organization is meeting or exceeding stakeholder expectations–positive expectational gaps–pressure to change is unlikely to emerge from organizations or stakeholders (Meznar, Johnson Jr., & Mizzi, 2006, p. 60).

In an alternative description of the development of issues, Vibbert (1987) argued that issues progress through four stages–definition, legitimization, polarization and identification. The media play active roles in the last two stages, polarizing two sides of the issue so that people feel forced to identify with one side or the other. When organizations delay public relations programs until the issue stage rather than beginning at the stakeholder or public stage, “they usually are forced to develop programs of crisis communication–especially when polarization occurs,” (Grunig & Repper, 1992, p. 149). McCombs (1977) warned that when “an issue is highly salient and opinions are largely shaped, public relations may be limited to a defensive posture or a redundant ‘me-tooism’” (p. 90). Organizations have less ability to influence issues when they become the focus of mass media coverage, legislation and/or litigation (Bridges & Nelson, 2000; Coates, Coates, Jaratt & Heinz, 1986; Heath, 1997; McCombs, 1977).

Because of the importance of conflict as a news value driving the selection and publication of news, the media are likely to cover issues when there is a high degree of public conflict between two parties (Karlberg, 1996). Concurrently, the involvement of the media in the issues of contention between organizations and their publics is certain to intensify the situation (Heath, 1997; Huang, 1997). Activists obtain credibility, resources and exposure for their positions by attracting media coverage, and therefore, media coverage is critical to their mobilization and effectiveness (Heath, 1997; Olien, Tichenor & Donahue et al., 1989).

Media interest adds legitimacy and longevity. Van Leuven and Slater (1991) proposed that the media have two roles in the development of issues: providing “running accounts of developing issue dimensions and events prompted by the issue” and providing “a description of how publics are organizing around an issue” (p. 166). Media coverage is an indicator of public interest and public opinion (Price, 1992), and continuing and intensive coverage of issues is indicative of persistent public interest. Greening and Gray (1994) found a positive association between firm-specific media attention and corporate resource commitments to public affairs management. “The corporate response may be to try buffering (altering external expectations or standards) or bridging (altering internal practices of standards), but as press coverage increases, most firms come under pressure to do something” (Meznar, Johnson Jr., & Mizzi, 2006, p.59).

More on activists and advocates

Activist groups rely on the attractiveness of their issues to garner and maintain members, and, as issues gain status, activist organizations gain attention, members and resources (Hrebnar & Scott, 1982; Schlozman & Tierney, 1986). Activists today are “focusing more on winning issues and seeking solutions, rather than merely creating awareness of problems,” (Regester & Larkin, 2005, p. 14). Activists are therefore more likely to pursue an issue that meets certain criteria including that the issue’s resolution will:

- Result in real improvement for people.

- Give people a sense of their own power.

- Be worthwhile and winnable.

- Be felt in an emotional way.

- Be easy to understand.

- Have a clear target and timeframe.

- Build leadership.

- Have a financially beneficial angle.

- Enhance profile to support subsequent campaigns.

- Raise money and membership.

- Fit with objectives and values.

Adapted by Regester & Larkin (2005, p. 14) from Organizing for Social Change, Midwest Academy, 2000.

Issues rise and fall in status on the public’s agenda (Crable & Vibbert, 1985; Downs, 1972; Hainsworth, 1990; Jones & Chase, 1979), and when issues appear to be resolved or otherwise fall from the public’s agenda, activist and advocacy organizations may lose relevance and therefore, resources. To survive, activist organizations must evolve with changes in their issues environments (Gans, 2003; Gitlin, 2001; Jopke, 1991; Ryan, 1991; Smith, 1996; Tuchman, 1997). Smith (1996) argued that activist groups must work to remain viable by monitoring and adjusting to the status of the issues they advocate. He proposed that activist collectives and social movement organizations be renamed as “issue organizations.”

Issue Pacesetters

According to Dawkins (2005), some organizations don’t wait for their industry to collectively respond to issues, but rather move deliberately or intuitively to take the lead. He argues that when an industry is confronted with an organization that uniquely remedies an issue–labeled an issue pacesetter–the issue management dynamic is quite different than when industry members act together to implement change, such as the self-imposed content ratings issue in the music industry. This is also true when an issue affects a single company. The issue pacesetter model comprises five steps: (a) changed stakeholder expectations, (b) issue pacesetter emergence, (c) heightened attention and pressure, (d) decision making under pressure, and (e) industry implementation and compliance (Dawkins, 2005).

The Issues Environment

The issues environment describes the portfolio or set of issues shared across an industry or other groups of organizations that are similar in terms of size, location, government regulations and other factors (Dougall, 2005). Many issues are not organization-specific and demand the attention of multiple organizations together with publics and other stakeholders. Such issues have collective significance and are contested by organizations individually and collectively as an industry or other grouping (Heath, 1997). For example, major issues for the pharmaceutical industry include access to drugs, drug safety, and drug pricing. These issues concern and affect most pharmaceutical companies simultaneously. Ways to measure and even predict change in the issue environment are still emerging, but some important principles are:

- The ebb and flow of issues comprising this issues environment can be tracked by describing the turnover of issues (stability), the number of issues (complexity), volume of media coverage (intensity) and favorability of that coverage (direction).

- The number of issues that can emerge (complexity) is not infinite and will reach saturation.

- Issues that emerge and compel public attention–including activists and the media–often remain for years. Issue-set inertia describes an environment in which the same issues persist over time while issue managers, even entire organizations, come and go (Dougall, 2005). Drug safety and drug pricing are examples of persistent issues that have outlasted many pharmaceutical companies.

- While issues are unlikely to emerge and be resolved quickly, what can and does often change dramatically in the issues environment is the intensity and favorability of public attention as new events and topics emerge.

- Activists and advocates typically have fewer resources than companies and governments and, therefore, a more limited voice in the issue environment. Their voices are more likely to attract attention when used to contend multiple, persistent issues. Activist and advocacy groups that can sustain pressure on organizations over time are typically institutionalized to some extent with employees to pay, equipment to lease, and multiple issues to contend.

- The issues that attract the most media coverage are most likely to be contended by the most influential, resource-rich organizations. Issues attracting attention more intermittently are those contended most vigorously by activists and resisted by organizations.

- Organizations may try to avoid sustaining an issue by refusing to engage in a public debate. However, this downplaying or buffering strategy often stimulates more conflict that the news media will happily report (Dougall, 2005).

Organizations, issues and publics

The sustainability of competitive advantages depends as much on an organization’s abilities to effectively negotiate non-market forces–issue and stakeholders–as on the effective satisfaction of “economically motivated constituents in the marketplace,” (Mahon et al., 2004, p. 170). While it is widely accepted that stakeholder behavior and issue evolution are interdependent, very little research explicitly addresses how managers deal with issues and stakeholders simultaneously (Mahon et al., 2004). To some extent, the relationship management approach to public relations has emerged from recognition of this divide between organizations, issues and publics. This gap creates both challenges and opportunities for those of us who want to advance the impact and value of issues management as a practice, a process and a field of scholarship.

References

Arringtion, C.B. & Sawaya, R.N. (1984). Managing public affairs: Issues management in an uncertain environment. California Management Review. (26)4, 148-160.

Arthur W. Page Society (2007). The Authentic Enterprise.

http://www.awpagesociety.com/site/resources/white_papers/. Accessed October 15, 2008.

Bridges, J. A., & Nelson, R. A. (2000). Issues management: A relational approach. In J. A. Ledingham & S. D. Bruning (Eds.), Public relations as relationship management: A relational approach to the study and practice of public relations. (pp. 95-115). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Coates, J. F., Coates, V. T., Jarratt, J., & Heinz, L. (1986). Issues and management. Mt. Airy, MD: Lomond Publishing.

Cheney, G., & Christensen, L. T. (2001). Public relations as contested terrain. In R. L. Heath & G. Vasquez (Eds.), The handbook of public relations. (pp. 167-182). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Chase, W.H. (1984). Issue management: Origins of the future. Stamford CT: Issue Action Publishers.

Chase, W. H. (1982, December 1). Issue management conference–A special report. Corporate Public Issues and Their Management, 7,1-2.

Dougall, E. K. (2007). The problematic public opinion environment. In B. E. Stuart, M. S. Sarow & L. Stuart (Eds.), Integrated business communication: In a global marketplace. (pp. 158-159). London: Wiley.

Downs, A. (1972). Up and down with ecology: The ‘issue attention cycle’. Public Interest, 12, 38-50.

Ewing, R. P. (1980). Evaluating issues management. Public Relations Journal, 36(6), 14-16.

Gans, H. J. (2003). Democracy and the news. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gans, H. J. (1979). Deciding what’s news. New York: Pantheon.

Griffin, J. J. (2005). The empirical study of public affairs: A review and synthesis. In Harris, P. and Fleisher, C. S. (Eds.) Handbook of Public Affairs.(pp. 458-480). London, UK:Sage.

Grunig, J. E., & Repper, F. C. (1992). Strategic management, publics, and issues. In J. E. Grunig, D. M. Dozier, W. P. Ehling, L. A. Grunig, F. C. Repper, & J. White (Eds.), Excellence in public relations and communications management. (pp. 117-157). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Grunig, L. A. (1992b). How public relations/communication departments should adapt to the structure and environment of an organization … and what they actually do. In J. E. Grunig, D. M. Dozier, W. P. Ehling, L. A. Grunig, F. C. Repper, & J. White (Eds.), Excellence in public relations and communication management. (pp. 467-481). Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Heath, R.L. (2006) A rhetorical theory approach to issues management. In C.H. Botan and V. Hazleton (Eds.), Public relations theory II.(pp. 63-99). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Heath, R.L. (2002). Issues management: Its past, present and future. Journal of Public Affairs,2(2), 209-214.

Jacques, T. (2005). Using best practice indicators to benchmark issue management. Public Relations Quarterly. Summer, 2005.

Jacques, T. (2000). Don’t just stand there: the do-it plan for effective issue management. Brunswick, VIC: Issue Outcomes.

Jopke, C. (1991). Social movements during cycles of issue attention: The decline of the anti-nuclear energy movements in West Germany and the USA. British Journal of Sociology, 42(1), 43-60.

Knight, G. ( 2007). Activism, risk, and communicational politics: Nike and the sweatshop problem. In S. May, G. Cheney, & J. Roper (Eds.), The debate over corporate social responsibility(pp. 305-318). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Mahon, J.F. (1989). Corporate political strategy. Business in the Contemporary World, 2(1), 50-62.

Mahon, J.F., Heugens, P.M.A.R., & Lamertz, K. (2004). Social networks and non-market strategy.Journal of Public Affairs, 4(2), 170-189.

McCombs, M. (1977, Winter). Agenda setting function of mass media. Public Relations Review,3, 89-95.

Olien, C. N., Tichenor, P. J., & Donahue, G. A. (1989). Media coverage and social movements. In C. Salmon (Ed.), Information campaigns: Balancing social values and social change. (pp. 139-163). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Palese, M. & Crane, T.Y. (2002). Building an integrated issue management process as a source of sustainable competitive advantage. Journal of Public Affairs, 2(4), 284-292.

Pratt, Cornelius B. (2001) Issues management: The paradox of the 40-year U.S. tobacco wars. In R. L. Heath & G. Vasquez (Eds.), The handbook of public relations. (pp. 335-355). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Price, V. (1992). Public opinion. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Public Affairs Council (2008). Accessed October 28, 2008.

http://pac.org/issues_management

Regester, M. & Larkin, J. (2005). Risk issues and crisis management: A casebook of best practice. Philadelphia, PA: Kogan Page.

Renfro, W.L. (1993). Issues management in strategic planning. Westport, CT: Quorum.

Scott, S. V. & Walsham, G. (2005). Reconceptualizing and managing reputation risk in the knowledge economy: Toward reputable action. Organization Science, 16(3), 308-322.

University of Southern California Annenberg Strategic Public Relations Center Public Relations (2007) Generally Accepted Practices Study (GAP IV) Survey, Los Angeles, CA:USC.http://annenberg.usc.edu/CentersandPrograms/ResearchCenters/SPRC/PrevGAP.aspx

Vibbert, S.L. (1987, May). Corporate communication and the management of issues. Paper presented at the meeting of the International Communication Association, Montreal.

Annotated Bibliography

Ashley, W.C. & Morrison, J.L. (1995). Anticipatory management: 10 power tools for achieving excellence into the 21st century. Leesburg, VA: Issue Action Publications.

A very accessible and practical issues management handbook that provides 10 “power tools,” including the issue life cycle, issues vulnerability audit, issue briefs, Delphi rating method, 10-step IM process, issue accountability model, issue analysis worksheet and scenario techniques. This book is an easy-to-read and well-organized resource that offers a well-considered and practical set of guidelines.

Arringtion, C.B. & Sawaya, R.N. (1984). Managing public affairs: Issues management in an uncertain environment. California Management Review, (26)4, 148-160.

Almost a quarter of a century has passed since Arrington and Sawaya argued in their still-relevant article that issues management “may be an unfortunate misnomer. Certainly, no corporate staff function can manage a public issue to a corporation’s desired conclusion with any regularity” (1984, p. 148). For an overview of issues management, this article is succinct and relevant despite its age. The authors argue that the process of issues management functions “to organize a company’s expertise and enable it to participate effectively in the shaping and resolution of public issues that critically impinge upon its operations” (p. 148).

Cheney, G., & Vibbert, S. L. (1987). Corporate discourse: Public relations and issues management. In F. Jablin, L. Putnam, K. Roberts, & L. Porter (Eds.), Handbook of organizational communication: An interdisciplinary perspective. (pp. 165-194). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

For those who are interested in exploring critical rhetorical perspectives on issues management, Cheney and Vibbert provide an excellent foundation discussion in which they argue that corporate public discourse serves to blur the publicly shared distinctions between organization and environment–“us” and “them.” This discourse creates opportunities for organizations to redirect and resituate concerns about issues in ways that serve the organizations’ interests.

Griffin, J. J.(2005). The empirical study of public affairs: A review and synthesis. In Harris, P. and Fleisher, C. S. (Eds.) Handbook of public affairs. London, UK: Sage.

Griffin reviews and synthesizes key contributions from many diverse empirical studies on public affairs and corporate political activities over the past four decades. This work provides a comprehensive review of public affairs literature, which also identifies where empirical research gaps in the field. The chapter presents three waves of research on corporate public affairs and corporate strategy: (1) foundational building blocks, (2) managerial challenges, and (3) blurring of boundaries. Issues management is considered in the second research wave, and includes a review of the literature on issues management strategies for public affairs and concepts such as the issues life cycle.

Griffin, J. J., Fleisher, C.S., Brenner, S. N., and Boddewyn, J. J. (2001) Corporate public affairs research: Chronological reference list, Part 1: 1985-2000, International Journal of Public Affairs, 1(1): 9-32. AND

Griffin, J. J., Fleisher, C.S., Brenner, S. N., and Boddewyn, J. J. (2001) Corporate public affairs research: Chronological reference list, Part 2: 1958-1984, International Journal of Public Affairs, 1(2): 167-186.

As the title suggests, these works provide an essential foundation of resources for the scholar or practitioner of public affairs in general and, more specifically, issues management. Griffin and her co-authors assembled a resource list encompassing the literatures of corporate public affairs, political strategy, issues management, international public affairs, community relations and political involvement activities (including political action committees, lobbying, grassroots organizations, etc.) to create a wide-ranging bibliography.

Heath, R. L. (1997). Strategic issues management: Organizations and public policy challenges. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

An essential resource for practitioners and scholars, Heath’s issues management text provides a rich and challenging examination of the discipline from a strategic management perspective. He contends that issues management is effective when it supports strategic business planning and moves public relations closer to management. He emphasizes the essential role of corporate responsibility and the interplay between effective issue stewardship and collaborative decision-making with communities and other stakeholders. Note that a second edition (2008) is now available.

Heath, R.L, & Coombs, W.T. (2006). Today’s public relations: An introduction, Sage, Thousand Oaks: CA

For an excellent overview of the practice see chapter 10–Monitoring and Managing Issues, pp. 258-302. The authors provide issues communication strategies, tips and advice for best-practice issues communication efforts and enterprises. The focus is on communication strategy rather than messaging. A worthwhile extension of this chapter is the “professional reflection” section by Tony Jacques entitled ”The Brilliant Evolution of Issue Management.”

Heath, R.L. (2006). A rhetorical theory approach to issues management. In C.H. Botan and V. Hazleton (Eds.), Public relations theory II.(pp. 63-99). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Heath provides a survey of the leading commentary on issues management and explores its theoretical underpinnings. Topic areas explored include issues management definitions and theoretical underpinnings, implications of these for future research and theory development, and a discussion of the implications of the theory and research of issues management practice in conjunction with public relations and public affairs.

Heath, R. (2002). Issues management: Its past, present and future. Journal of Public Affairs,2(2), 209-214.

In this issues management-focused edition of the Journal of Public Affairs, Heath explores the foundations of contemporary issues management and argues that the discipline today is most appropriately defined as stewardship for building, maintaining, and repairing relationships with stakeholders and stakeseekers. He argues that issues management is the proactive application of (1) strategic business planning, (2) getting the house in order, (3) scouting the terrain, and (4) strong defense and smart offense.

Jacques, T.(2006). Activist “rules” and the convergence with issue management. Journal of Communication Management, 10(4), 407-420.

Jacques makes a timely and convincing argument that the advent of the Internet has expanded the area of common ground between activists and corporate communicators. Focusing on Saul Alinsky’s rules for radicals (1971), the author explores the parallels between modern activism and corporate issue management. This is useful for practitioners and scholars alike.

Jacques, T. (2005). Using best practice indicators to benchmark issue management. Public Relations Quarterly. Summer, 2005.

This article reports key findings from the Issue Management Council Best Practice Project, led by Jacques. Nine best practice indicators are advanced. This is an essential resource for practitioners looking for important and accessible advice on evaluating and organizing their issues management activities. This is also a great article to share with your management team.

Jacques, T. (2002). Towards a new terminology: Optimizing the value of issue management.Journal of Communication Management, 7(2), 140-147.

Issues management is evolving from a reactive crisis prevention tool to a maturing strategic management discipline. Contending that the terminology of issue management has not kept pace with the discipline’s evolution, Jacques proposes an alternative, “less limiting” lexicon.

Jacques, T. (2000). Don’t just stand there: the do-it plan for effective issue management. Brunswick, VIC: Issue Outcomes.

In this slim volume, Tony Jacques provides a masterful, user-friendly tool to simplify planning, managing, implementing, and evaluating strategies and tactics to deliver impact on significant issues. This is a must-have practitioner resource.

Knight, G. ( 2007). Activism, risk, and communicational politics: Nike and the sweatshop problem. In S. May, G. Cheney, & J. Roper (Eds.), The debate over corporate social responsibility.(pp. 305-318). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Using the Nike sweatshop case, Knight provides a comprehensive and critical dissection of Nike’s response. He argues that when large corporations like Nike are confronted with claims of systemic problems, their issues management machinery effectively respond by transforming problems (systematic labor exploitation) into issues (a complex global labor market where Western ideals in relation to child labor and other issues may not fit). “To transform a problem into an issue is to play down its problematic character while acknowledging that there is something–a topic or question–that needs to be addressed, especially discursively” (Knight, 2007, p. 313). Knight contends that issues are actually “problems that have been neutralized to some extent by making them into matters of common interest and concern, amenable to negotiation and reform” (p. 313). Knight’s discussion is compelling and thought-provoking.

Larkin, J. (2003). Strategic reputation risk management. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

In this accessible, well-organized and practitioner-friendly book, Larkin argues that the ability to recognize the threats and opportunities around current and emerging reputation risks should be treated no differently from the way in which any operational risk is identified, assessed and mitigated against (2003, p. 272). While the term “issues management” is avoided in favor of “risk issues” and “reputation risk,” the issue life cycle model is described, as are other aspects of issues management practice. Larkin addresses the value of reputation, the origins of risk issues, the assessment of risk issue impact, and models and systems for identification, prioritization, assessment and response. Key concepts are effectively illustrated in figures and charts embedded throughout the text.

Mahon, J.F., Heugens, P.M.A.R., & Lamertz, K. (2004). Social networks and non-market strategy.Journal of Public Affairs, 4(2), 170-189.

Business and society scholar John Mahon, teams up with Lamertz and Heugens to argue that social network analysis has the potential to enrich and integrate theoretical perspectives to explore how managers should deal with issues and stakeholders simultaneously. Public relations scholars have made similar arguments about the place of relationship management. The article provides interesting insight into the parallel, but different approaches business strategy scholars take to address similar challenges in applied and theoretical research.

Palese, M. & Crane, T.Y. (2002). Building an integrated issue management process as a source of sustainable competitive advantage. Journal of Public Affairs, 2(4), 284-292.

Highly recommended for practitioners, this article is written by two of the field’s most experienced consultants. Palese and Crane provide explain how to build an issues management process.

Regester, M. & Larkin, J. (2005). Risk issues and crisis management: A casebook of best practice. Philadelphia, PA: Kogan Page.

Written by two leading United Kingdom practitioners, this book provides a collection of accessible and practical models and tips. While the rationale for the term “risk issues” rather than issues is not satisfactorily explained, the book includes chapters and resources directly and indirectly relevant to issues management.

Scott, S. V. & Walsham, G. (2005). Reconceptualizing and managing reputation risk in the knowledge economy: Toward reputable action. Organization Science, 16(3), pp. 308-322.

A must-read scholarly treatise on the subject of the concept and practice of reputation risk. “Reputation is emblematic of the kind of resource that managers have to learn to work within the knowledge society. It is ‘weightless’ (Quah, 1998, 1999), informational, abstract, and intertwined with global media” (Scott & Walsham, 2005, p. 309). They argue that the “determination to identify present risk and its causal factors, measure it, benchmark it and thereby neuter it,” is flawed (p. 309) and that firms should resist the temptation to automate reputation risk assessment using, for example, incident databases that track events and monitor media. These approaches, they contend, are “mainly reactive, only scratching the surface of the complex status and nature of reputation risks” (p. 309). The authors propose a reconceptualization of reputation risk that not only incorporates a more sophisticated view of reputation, but also acknowledges the role that risk and trust relations can play in its constitution.

Seeger, M.W., Sellnow, T.L. & Ulmer, R.R. (2001) Public relations and crisis communication: Organizing and chaos. In R. L. Heath & G. Vasquez (Eds.), The handbook of public relations. (pp. 335-355). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Primarily focused on crisis communication, the authors address the relationship between crisis communication and issues management, arguing that “by investigating issues with the potential for crisis, public relations specialists are better able to diffuse some crises before they erupt through dramatic trigger events” (Seeger, Sellnow, & Ulmer, 2002, p. 156).

Smith, M. F., & Ferguson, D. P. (2001). Activism. In R. L. Heath & G. Vasquez (Eds.), The handbook of public relations. (pp. 291-300). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

The authors provide a comprehensive and accessible review of the literature on activism. They advocate for continued research into activism and the interaction between activists and other organizations, as well as for greater methodological diversity in studying the interaction between activists and other organizations.

Thank you for your article it’s really nice. I have a blog which is speacking about that. Check it !

I have added your link to my blog here http://tinyurl.com/Convresources ,Some genuinely interesting points you have written. Assisted me a lot, just what I was searching for : D.

Very informative and extensive; unfriendly background but all in all it passes the message well. congratulations

David