Download Full Paper: How Narratives Can Reduce Resistance and Change Attitudes

Abstract: This article outlines the importance of new and emerging behavioral insights research for the public relations profession. How attitudes and beliefs are cultivated, processed and then potentially changed through communicative activities are outlined and connections draw to the practice. Research from the fields of cognitive and behavioral science, neuroscience and psychology also detail the types of resistance that intended audiences cognitively employ to counter behavioral and attitude change. Finally, the power and persuasive influence of narrative communication is also discussed and examined as it relates to the fields of crisis management, health communication, public policy issues and consumer behaviour.

Persuasive communication is at the heart of public relations. While industry professionals continue to successfully change attitudes and behaviours, research in the fields of social cognition and neuroscience are beginning to reveal the underpinnings of this communication. This new understanding is invaluable for improving the practice of public relations because it illustrates why some communications are successful while others are not. As the literature continues to grow, research on the different aspects of communication have started to intersect, providing a more integrated perspective of communication. Focusing on the interactivity of factors continues to be important for the literature to explain the complex nature of communication seen by industry. The advancements in methodology, such as new modelling and imaging techniques, create new possibilities for research and subsequently, application in an industry setting. It is often a reciprocal relation between research and industry, with new applicable industry practices emerging from research, and new directions for research emerging from industry.

The purpose of this paper is to connect the growing research in the fields of cognitive and behavioral sciences, neuroscience, and psychology with the theory and practice of public relations, with the intention of adopting and potentially applying some of the newer methods of measuring cognition and attitude formation as a means of assisting the practice and the profession in achieving more effective behavorial outcomes in public relations campaigns. This paper will outline a number of important and relevant theories that have tested the impact of narrative-based persuasion strategies and provide new evidence for communicators to use in their current and future campaigns. Following this review a number of insights for practices such as crisis management, health communications, public policy initiatives and consumer products are discussed

Cultivating Behavioural Communication

Presenting a message is only the beginning of effective communication. In public relations, where the goal is to drive both thought and action in a particular direction, the internal processing of the content determines the changes in an individual’s attitudes, beliefs and intentions. This internal processing of communication has long been a central focus for researchers in the fields of social cognition.

With the rise of mass media, questions of its effects on attitudes and behaviour began to emerge. Gerbner (1990;1998), in his cultivation theory, posited that exposure to mass media can skew the viewer’s perspective of the real world towards that portrayed in media. This “cultivation” can have two effects: (1) first order effects, effects on our judgments; and (2) second order effects, changes to beliefs and attitudes. In other words, Gerbner was concerned with how people who were heavy viewers of mass media, in this case television violence from nightly newscasts, impacted the viewers judgments and perceptions of the ‘real world’ and whether their attitudes and behaviors changed as a result of these perceptions. Subsequent explanations of these effects were grounded in the research of Tversky and Kahneman (1974) on heuristics, mental shortcuts used to make processing of stimuli more efficient. While economical, heuristics are not always optimal and can be problematic for decision-making on a micro individual level, and a macro organizational level. A longitudinal study of corporate headquarters revealed that heuristics lead to cognitive biases, such as risk aversion and overconfidence, in strategic security decisions, which could be detrimental to organizations (Workman, 2012). Research in heuristics, how we make quick judgments through mental shortcuts, would pave the way for the new discoveries tying communication, persuasion, and cognition.

Shrum and O’Guinn (1993) proposed a heuristic processing model in which an individual’s perceptions of the world aligned more closely with the media through heuristic processing. This means that through commonly held beliefs, individuals judge the real world prevalence of scenarios, based on readily available mental models, such as perceptions of increased violence, which can be skewed by media exposure. Shrum (1996) also suggested other heuristics, such as simulation or representativeness, as having an effect on how accessible certain information appears to us. Easily simulated or prototypic scenarios are more accessible and therefore used for judgement of world. Shrum and O’Guinn’s (1993) created the heuristic processing model as a dual-process theory. These cognitive models suggest that when motivation or mental resources are low, a quick, but occasionally erroneous, processing is used. During this type of processing, individuals rely on heuristic cues to evaluate a message’s content. For example, the quality of the message’s content may be judged based on peripheral attributes like delivery or communicator qualities. Alternatively, highly motivated individuals will engage in resource-intensive processing of the message, known as central, systematic, rational or critical processing. All three models seek to explain persuasive communication through the selection of processing and subsequent application of mental resources (Shrum, 2004). Depending on the type of processing selected and where resources are put towards, a message can affect an individual in very different ways.

Resistance to Public Relations Messages

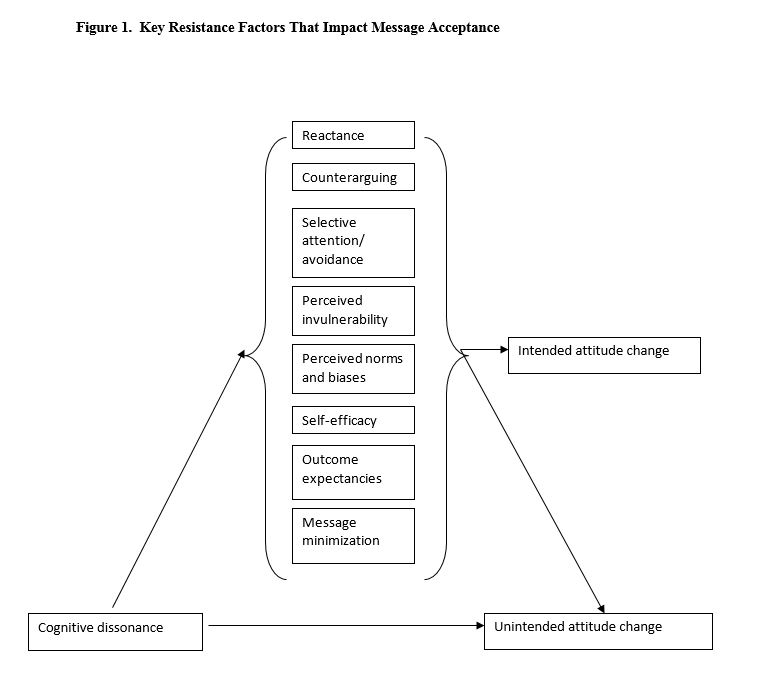

A major challenge that public relations continues to face is message resistance (see Figure 1). No matter how well presented a message may be, if the receiver actively resists the message, the desired change in attitude or behaviour will not be seen. Resistance is the devotion of cognitive resources toward processes that oppose the message. It can take various forms, such as counter arguing in which the receiver generates inconsistent and opposing thoughts toward the message’s content. It is even possible that failed attempts at persuasion will make the success of future attempts more difficult because resistance can be self-reinforcing. An example of the backfire effect, in which messages produce a reversal of the intended effects, is the communication of climate change mitigation policies. Hart and Nisbet (2012) found a lack of correlation between knowledge of climate change and support for mitigation policies, meaning that simply providing more factual information regarding the issue did not reliably change attitudes in favor of mitigation and in some cases, it had the opposite or a boomerang effect on its intended audience.

Resistance often emerges when an individual faces cognitive dissonance, the anxiety of contradictory thought. This anxiety can occur when new information opposes or threatens one’s worldview, and also when one’s attitude contradicts one’s behaviour (Festinger, 1962). Cognitive dissonance, which is a state of mental uneasiness, discomfort or imbalance one feels when you expect a contradictory attitude or opinion, can be exemplified by how lenient individuals can be when politicians from parties they support are revealed to be corrupt (Anduiza, Gallego & Munoz, 2013). Political identification encompasses a wide range of values, making it difficult to change. When confronted with knowledge of corruption, individuals must change their attitude toward the politician or their political identification. By being more lenient of such behaviour, their affiliation with the politician becomes more cognitively sound. If an opposing party’s politician did the same, the judgement would be very different. However, individuals can differ in how they experience dissonance and how they deal with it. In the example of partisanship biasing attitudes towards corruption, Auduiza, Gallego & Munoz (2013) found that political awareness moderated the effect. Highly informed and aware individuals were less likely to judge the same wrongdoings differently as those from different political parties.

When a communication message produces dissonance, individuals seek to resolve the resulting mental discomfort through resistance or by rationalizing or changing their attitudes or behaviour. For example, hotels are actively attempting to minimize the washing of guest towels by encouraging guests to reuse bath towels during their stay. The message that is often used is one of environmental care through the reduction in water use. A guest who agrees with this attitude will likely hang their towels for reuse, while another, who resists this message as a way for the hotel to save money (and not the environment), leaves the towels to be cleaned daily, believing that they have paid for clean towels in their daily room rate. In many cases, the latter can be difficult because of the expensive cognitive load of overcoming the inertia of the status quo. For communicators trying to persuade a change in their receivers, cognitive dissonance can be a challenge, but not necessarily bad. It is merely the mental response to dealing with something that doesn’t fit one’s worldview. The intended result of communication can often arise from the subsequent attitude change in response to cognitive dissonance. The obstacle for public relations professionals lies in identifying and overcoming message resistance.

Narrative Persuasion

The benefit of understanding and accessing research from other fields for public relations professionals often lies in its ability to make sense and give evidence to notions that we already know intuitively. People have always known about the persuasive, whether intended or unintended, power of storytelling. However for many it is often difficult to express or explain why certain stories have more powerful effects than others. Persuasive narratives are those that can direct cognitive resources toward processing the narrative elements and away from resistance. The deeper an individual delves into the story, the less time and energy they have to actively oppose the message (Green & Brock, 2000). The experience of identification, transportation, and social proliferation establishes the depth of this narrative engagement. To resolve the cognitive dissonance, individuals begin to change their attitude to one that is more consistent with the new information in their mental framework. As research continues to reveal how we are affected through narrative persuasion, public relations practitioners can implement new research-based practices to improve the efficacy of their message.

The most obvious for professionals is, through formative research, to measure the degree of resistance in your intended audiences to your communication messages: what counter arguments are being used by those opposing the proposed change; does your audience believe that they can achieve the change that is desired; to what degree to their perceived biases limit them from the potential change. Specific research into communication in the fields cognitive behavior and psychology reveals both new understandings of persuasion and highlights potential areas for change in industry. Controlled experiments and analysis of case studies provide insights into the many applications of narratives in public relations, demonstrating how public relations industry can use narrative persuasion for different goals, from dispelling misconceptions and the resistances that maintain them, to integrating new information in a cognitively sound manner (Meisel & Karlawish, 2011). Organizations can implement narrative persuasion at all levels of communication, including email, social media, press conferences, and more (Weberling, 2012).

Crisis Management

As technology advances, new venues for communications emerge. Organizations often adopt these new channels to remain relevant and competitive, but research suggests that they may not be doing it effectively. One of the biggest recent changes in public relations is the rise of social media. However, research suggests that many fail to use social media well. Ki and Nekmat (2014) examined the use of Facebook for crisis management by Fortune 500 companies. Crises threaten the perception of an organization and often lead to negative outcomes, such as loss of reputation, if not handled properly (Yang, Kang & Johnson, 2010).

The objective of crisis management is to limit the impact that a crisis can have on the effected stakeholders and organizations (Coombs, 2014). Understanding the specific nature of the crisis is crucial as it dictates the appropriate type of crisis response. Apologies seek to rebuild or reinforce their reputation through compensation, highlighting previous successes, or playing the victim (Liu, Austin & Jin, 2011). Denials, on the other hand, diminish the responsibility of the organization through generating excuses, justifying actions, or ignore accusations. The most appropriate response is the one with a level of accommodation that matches the perceived degree of responsibility. When people believe the organization is responsible for the crisis, apologies are better suited. Ki and Nekmat (2014) found that over half of the Fortune 500 companies they studied employed an inappropriate crisis response via social media. In most of those cases, organizations gave the impression of greater organizational responsibility than they should have. The message format and communicator choice correspond to the response type to maximize crisis mitigation. Apologies are better conveyed as narratives, having the receiver connect with the communicator and redirecting cognitive resources towards processing the narrative elements. Denials, on the other hand, are better presented in a didactic, informational form because they convey a lack of guilt and reduce cognitive dissonance (Van Laer & De Ruyter, 2010). Apologetic and supportive crisis responses are more likely accepted when they are communicated by a third-party source, whereas denial-based, defensive crisis responses are more likely accepted when they are communicated by an organization representative (Liu, Austin & Jin, 2011).

Crises, according to Coombs (2014) “threaten to disrupt the operations of an organization” and “also involved a clear threat of potential harm to stakeholders” often do not end at the initial or immediate response. It is as important to maintain efforts to ensure message receivers undergo the intended attitudinal effects. Of the 28 companies, Ki and Nekmat (2014) examined, only nine replied to initial communication response from receivers. The lack of dialogue can be damaging to both persuasive attempts, and organizational reputation. Openness towards and support of dialogue is an important communicator quality that receivers consider when evaluating trust. Engaging in dialogue leads to more positive outcomes. Research examining the efficacy of current practices provides invaluable insight on what is being done well and what is not.

Health Communication

Health communication is a field in particular that can benefit greatly from recent research in narrative persuasion. Many health issues are persistent due to their complexity and the resulting inertia; shifting way from pre-existing unhealthy attitudes can be too demanding and difficult for most people. When dealing with health-related, behavioral change messages, many individuals respond with resistance to the recommended change. One potential method to overcome resistance is through the development of narrative-based, persuasive communications – in popular terms, this is often called ‘storytelling’. However as will be shown in examples below, in order for the narratives to be effective they must address the following: the general resistant messages that the intended audiences might already possess; the ability for the audience to believe that they are part of the referenced group; and thirdly, that they hear the same story through different communication channels within their identified influence communities.

The issue of social determinants of health in general is one of great concern due to inadequate focus and public support toward addressing it (Lundell, Niederdeppe & Clark, 2013). Without greater awareness and understanding, socioeconomic health disparities continue to grow (Gollust & Cappella, 2014). The difficulty lies in conveying the complexity and interactivity of individual and social factors determining health. The tendency to want to simplify issues to reduce cognitive load undermines efforts to deal with the underlying issues. Lundell et al. (2013) compared the use of narrative versus data or numeric images and found that narratives were able to effectively communicate causality, complexity, and interactivity better than images. Numeric-based images also invoked a sense of oversimplification that often lead receivers to reject the message. Examining communication regarding the obesity epidemic, Niederdeppe, Shapiro, and Porticella (2011) demonstrated the use of narratives to reduce resistance to messages based on the who the receiver believes is responsible for the cause of obesity. In order to change attitudes toward obesity and lower obesity rate, both individual and societal causes need to be addressed. Despite the need for individual action and policy reform, there is an insufficient understanding of the social problems that perpetuate obesity. Narratives were more effective at changing beliefs of the societal causes of obesity than a simple detailing of facts or leading causes of the disease and as a result, less counter arguing — the rejection of a message through the production of inconsistent and opposing thoughts towards a message’s content — by the receiver was observed. Although health professionals often avoid individual anecdotal narratives, growing evidence suggests that a purely evidence or data-based approach is insufficient. It is necessary to promote acceptance of evidence-based practices and narrative persuasion is a powerful tool to achieve that (Meisel & Karlawish, 2011).

The distinct ability of narratives to elicit a greater emotional response can be useful for communicating to more vulnerable or resistant populations (Yoo, Kreuter, Lai & Fu, 2013). Narratives are able to engage and reach those who are less involved or aware, through social proliferation — the transfer of the message through a cultural community. Social proliferation is achieved through culturally-relevant discussion, reinforcement and support (Larkey & Hecht, 2010). When designed with cultural relevancy in mind, narratives can resonate with the social values of a particular group, promoting a deeper understanding and the dissemination of a message through the community (Miller-Day & Hecht, 2013). Testing the effect of negative emotions in breast cancer narratives directed at low-income African women, Yoo et al., (2013) found the use of sadness in messages to reduce the effect of counterarguing, while increasing attention and message recall, through the process of empathy. McQueen, Kreuter, Kalesan, and Alcatraz (2011) also found narrative to be more effective at reducing counter arguing and producing long-lasting attitude change toward breast cancer and the perceived importance of mammograms. Successful has also been seen in experiments that use video narratives from survivors to communicate various issues like coping, treatment, and healthcare experience, as measured their attitudes toward them (Kreuter et al., 2010; Perez et al., 2014)

Various HIV presentation projects have began to employ narratives as a form of behavioural communication to address the gap between knowledge and attitude (Petraglia, 2009). The Modeling and Reinforcement to Combat HIV/AIDS program, or MARCH, utilizes role model narratives in the form of serialized dramas to promote discussion and dialogue on HIV prevention and treatment in Ethopia. The Reflection and Action Within Most-at-Risk Populations program, or RAMP, targets HIV-at-risk populations in Laos and Thailand and combines narratives with individual and group activity with facilitators to develop more personal and community relevancy.

Adolescent health education is another area of health communication where behavioural communications methods, like narrative persuasion, can be more effective that current efforts. Existing school-based approaches tend to fail at eliciting meaningful knowledge acquisition and behaviour change. Grabowski and Rasmussen (2014) found that authentic communicators, those who could communicate the relevancy of the information, were more admired and respected. Through narratives and dialogue, participants were able to better understand the real life context of the concepts and apply them to their individual sense of self and world. Miller-Day and Hecht (2013) examined the narrative engagement framework behind the “Keepin’ it REAL” school-based substance abuse prevention initiative. With the goals of mental framework building, change, and maintenance in mind, the program uses narratives from peers to enhance identification and personal relevance. The process involves collecting narratives, analyzing them, gathering input from study participants, developing the presentation of those narratives, and designing a curriculum around them. The success of such initiatives can be evaluated using scales like the perception of narrative performance scale (Lee, Hecht, Miller-Day & Eleck, 2011) which assesses the perceptions of narrative health messages based on the level of interest, the sense of realism, and the identification with the characters in the narrative.

Regarding the anti-vaccination movement, research has found that neither information explaining the lack of evidence behind the vaccine-autism connection or emphasizing the dangers of preventable disease, like measles, increased parents’ intention to vaccinate their children (Nyhan, Reifler, Richey & Freed, 2014). In this case, knowledge and awareness is rarely enough to insight meaningful attitude and behaviour change. Using research on decision-making and behavioural communication, decision aids can be developed for dealing with different health issues. These aids would assist with the cognitive demand of rationally processing and evaluating new information (Connolly & Reb, 2012). By helping integrate the information into pre-existing mental frameworks, individuals are no longer overwhelmed by the task of decision-making or using resistance to respond to the messages. The approach to such aids would involve a tiered approach to cater to the varying needs for assistance. At the simplest levels, new information, like doctor recommendations on vaccination, is provided. Later levels would involve presenting support materials, like visuals and narratives, interactive personal decision-making models, and outcome probability estimates.

Narrative persuasion has the potential to change unintended, but negative and undesired, attitudes from media exposure. Kimmerle and Cress (2013) demonstrated that individuals who viewed a documentary film on mental illness (schizophrenia) acquire more knowledge about the illness than those research participants that viewed a fictional film about the same disease, despite both films portraying the exact same information. The same principles of narrative persuasion can be used to produce a desirable attitude change where more experiential approaches have failed. Volkman and Parrott (2012) also determined narratives to be an effective channel for communicating issues regarding osteoporosis, while other researchers found the same for spinal cord injury rehabilitation (Smith, Papathomas, Martin Ginas, & Latimer-Cheung, 2013).

Another application of these findings is to design behaviour change support systems that integrate communication with technology. Doing so provides a platform for individuals to engage with messages in a meaningful way. The goal is to support particular behavioural change, like healthy eating, through forums, messaging and social networks, established by credible communicators (Drozd, Lehto & Oinas-Kukkonen, 2012). The key to gaining the desired behavioral change, through computer-mediated systems, is an effective dialogue-based support system. “Through dialogue support, users received appropriate feedback and counseling, which keeps them motivated, engaged, and involved in their change process” (p. 165). This can be achieved by embedding real-time support systems into the computer-based application which is readied to engage participants in a more active and trustworthy manner.

Public Policies

Public policies communication is another field that faces message resistance and growing polarization. Embedded political and interest-group opposition creates the conditions for cognitive confusion among those that are attempting to form opinions or change their attitudes on a give issue. Therefore persuasive and credible public information campaigns are crucial because misinformation can easily lead to poor decision-making by governments and regulator agencies. For example, public perceptions of energy consumption and saving strategies are largely inaccurate (Attari, DeKay, Davidson & de Bruin, 2010). Depending on the choices given and the consumers’ understanding of the benefits of the choice, energy efficiency appeals can have a reverse effect on attitudes towards energy-saving and energy use behaviour. Some households even consume more after such appeals (Sunstein & Reisch, 2013) given more inexpensively perceived alternatives – the cost-switching argument versus the environmental protection argument doesn’t appear to persuade enough consumers to change their behavior. By diverting cognitive resources away from processing resistance, narratives can both convey important information and help receivers integrate the information without dissonance, through identification and engagement with the message. Narratives on climate change that elicit identification and a close social bond can rally support for mitigation policies (Hart & Nisbet, 2012). Narrative persuasion has also been shown to be effective at communicating other complex public policy topics, such as immigration, stem cell research, and gay rights (Boswell, Geddes & Scholten, 2011; Stewart, 2013; Zhang & Min, 2013)

Consumer Industry

Public relations practitioners can also use behavioural communication principles when communicating about products and services to consumers. One particularly difficult task is promoting really new products or RNPs (Feiereisen, Wong & Broderick, 2013). Consumers often lack the proper mental framework to properly understand the benefits, leading to reliance on heuristics – mental shortcuts to help individuals make decisions requiring less cognitive processing — and cognitive biases that can misrepresent a product, service, or organization. By using analogies, consumers can map the new information onto a familiar framework. Another potential solution is to have consumers engage in mental simulations to reduce uncertainties toward the product. Research in this area has found that the optimal communication depends on matching the type of product with the right strategy. Hedonic products – products from which consumers drive certain types of pleasures, (i.e., fast cars, exotic vacations, high-fashion) are best conveyed by using visual mental simulations, while utilitarian products are best conveyed using verbal analogies (Feieresien, Wong & Broderick, 2013). While communicating new products can be a struggle, so can competing with existing products (Sunstein & Reisch, 2013). Researchers in the area of behavioural economics refer to the consumer’s passive choices and behaviour as the default rule. For example, environmentally friendly, “green” products may struggle when consumers already adopted non-environmentally friendly, “gray” products as the default rule. Default rules tend to persist due to endorsement, inertia, and risk aversion. It can be cognitively expensive to evaluate and make decisions regarding new choices. The default rule is often supported by others and therefore the safe one in terms of risk aversion. Through effective behavioural communication, communicators can reduce the cognitive load and shift the default rule in their favour.

When discussing the use of behavioral communication like narrative persuasion, it is important to keep in mind the ethical considerations. Although narratives can be effective at persuasion through overcoming resistance, overtly persuasive communications are often discounted as being disingenuous, unethical or manipulative (Dahlstrom & Ho, 2012). Narrative persuasion is not an infallible guarantee, but rather a tool that authentic and credible communicators need to recognize and employ. It is already being used to change attitudes, even in many cases unintentionally, because people have an intuitive desire to communicate stories. Through research, an understanding of how to best communicate stories emerges.

Future Directions

Through this research, it became evident that cognitive processes underlie and shape the outcomes of communication. By understanding how the brain processes communicative stimuli, we can better understand why some attempts at persuasion are unsuccessful. Part of the understanding is unraveling the biological underpinnings behind these cognitive mechanisms. With the help of new brain imaging techniques, researchers reveal another layer of depth to our understanding of the human mind, just as discoveries in cognition did in the past and continue to do in the present. Other future directions include improving measures of communication effectiveness and strategies for responding to receivers. Considering the importance of dialogue and maintaining relationships, the communicator’s job doesn’t end with the message. Research into how receivers respond to messages, such as the subsequent attitude changes or resistance, can dictate how communicators follow-up either to curb unintended effects or sustain intended ones. Continuing to expand our understanding of social brain will provide new strategies and methods for public relations, as well as a sense of clarity when dealing with the complex workings of communication.

Acknowledgments:

Funding for this article was provided through a grant from the Institute of Public Relations in 2014, as part of the IPR’s Behavioral Insights Research Center. The funding allowed for the hiring of research assistant, Tim Li, who played an important role in gathering the necessary literature and to assist with shaping the initial insights on this research study. I would also like to thank the valuable comments from the three reviewers who provided thoughtful and constructive advice on the manuscript. This is the first in a series of papers on the connection between behavioral science research and public relations theory and practice.

References

Anduiza, E., Gallego, A., & Muñoz, J. (2013). Turning a lind eye experimental evidence of partisan bias in attitudes toward corruption. Comparative Political Studies, 46(12), 1664-1692.

Attari, S. Z., DeKay, M. L., Davidson, C. I., & de Bruin, W. B. (2010). Public perceptions of energy consumption and savings. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(37), 16054-16059.

Boswell, C., Geddes, A., & Scholten, P. (2011). The role of narratives in migration policy‐making: A research framework. The British Journal of Politics & International Relations, 13(1), 1-11.

Chaiken, S. (1980). Heuristic versus systematic information processing and the use of source versus message cues in persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(5), 752.

Cho, H., Shen, L., & Wilson, K. M. (2013). What makes a message real? The effects of perceived realism of alcohol-and drug-related messages on personal probability estimation. Substance Use & Misuse, 48(4), 323-331.

Coombs, W.T. (2014). State of crisis communication: Evidence and the bleeding edge. 1(1).

Connolly, T., & Reb, J. (2012). Toward interactive, Internet-based decision aid for vaccination decisions: Better information alone is not enough. Vaccine, 30(25), 3813-3818.

Dahlstrom, M. F., & Ho, S. S. (2012). Ethical considerations of using narrative to communicate science. Science Communication, 1075547012454597.

Fang, D., Fang, C. L., Tsai, B. K., Lan, L. C., & Hsu, W. S. (2012). Relationships among trust in messages, risk perception, and risk reduction preferences based upon avian influenza in Taiwan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9(8), 2742-2757.

Feiereisen, S., Wong, V., & Broderick, A. J. (2013). Is a picture always worth a thousand words? The impact of presentation formats in consumers’ early evaluations of really new products (RNPs). Journal of Product Innovation Management, 30(S1), 159-173.

Festinger, L. (1962). Cognitive dissonance. Scientific American, 207(4), 93–107.

Gerbner, G. (1990). Epilogue: Advancing on the path of righteousness (maybe). In N. Signorielli & M. Morgan (Eds.), Cultivation analysis: New directions in media effects research (pp. 249-262), Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Gerbner, G. (1998). Cultivation analysis: An overview. Mass Communication and Society, I, 175-194.

Gollust, S. E., & Cappella, J. N. (2014). Understanding public resistance to messages about health disparities. Journal of Health Communication, 19(4), 493-510.

Goodwin, J., & Dahlstrom, M. F. (2014). Communication strategies for earning trust in climate change debates. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 5(1), 151-160.

Grabowski, D., & Rasmussen, K. K. (2014). Authenticity in health education for adolescents: A qualitative study of four health courses. Health Education, 114(2), 86-100.

Green, M. C., & Brock, T. C. (2000). The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. Journal of personality and Social Psychology, 79(5), 701.

Hart, P. S., & Nisbet, E. C. (2012). Boomerang effects in science communication: How motivated reasoning and identity cues amplify opinion polarization about climate mitigation policies. Communication Research, 39(6), 701-723.

Ki, E. J., & Nekmat, E. (2014). Situational crisis communication and interactivity: Usage and effectiveness of Facebook for crisis management by Fortune 500 companies. Computers in Human Behavior, 35, 140-147.

Kimmerle, J., & Cress, U. (2013). The effects of TV and film exposure on knowledge about and attitudes towards mental disorders. Journal of Community Psychology, 41(8), 931-943.

Kreuter, M. W., Holmes, K., Alcaraz, K., Kalesan, B., Rath, S., Richert, M., & Clark, E. M. (2010). Comparing narrative and informational videos to increase mammography in low-income African American women. Patient Education and Counseling, 81, S6-S14.

Larkey, L. K., & Hecht, M. (2010). A model of effects of narrative as culture-centric health promotion. Journal of Health Communication, 15(2), 114-135.

Lee, J. K., Hecht, M. L., Miller-Day, M., & Elek, E. (2011). Evaluating mediated perception of narrative health messages: The perception of narrative performance scale. Communication Methods and Measures, 5(2), 126-145.

Liu, B. F., Austin, L., & Jin, Y. (2011). How publics respond to crisis communication strategies: The interplay of information form and source. Public Relations Review, 37(4), 345-353.

Lundell, H. C., Niederdeppe, J., & Clarke, C. E. (2013). Exploring interpretation of complexity and typicality in narratives and statistical images about the social determinants of health. Health Communication, 28(5), 486-498.

McQueen, A., Kreuter, M. W., Kalesan, B., & Alcaraz, K. I. (2011). Understanding narrative effects: The impact of breast cancer survivor stories on message processing, attitudes, and beliefs among African American women. Health Psychology, 30(6), 674.

Meisel, Z. F., & Karlawish, J. (2011). Narrative vs evidence-based medicine—and, not or. JAMA, 306(18), 2022-2023.

Miller-Day, M., & Hecht, M. L. (2013). Narrative means to preventative ends: A narrative engagement framework for designing prevention interventions. Health communication, 28(7), 657-670.

Murphy, S. T., Frank, L. B., Chatterjee, J. S., & Baezconde‐Garbanati, L. (2013). Narrative versus nonnarrative: The role of identification, transportation, and emotion in reducing health disparities. Journal of Communication, 63(1), 116-137.

Niederdeppe, J., Bigman, C. A., Gonzales, A. L., & Gollust, S. E. (2013). Communication about health disparities in the mass media. Journal of Communication, 63(1), 8-30.

Niederdeppe, J., Shapiro, M. A., & Porticella, N. (2011). Attributions of responsibility for obesity: Narrative communication reduces reactive counterarguing among liberals. Human Communication Research, 37(3), 295-323.

Niederdeppe, J., Shapiro, M. A., Kim, H. K., Bartolo, D., & Porticella, N. (2014). Narrative persuasion, causality, complex integration, and support for obesity policy. Health Communication, 29(5), 431-444.

Nyhan, B., Reifler, J., Richey, S., & Freed, G. L. (2014). Effective Messages in Vaccine Promotion: A Randomized Trial. Pediatrics, 133(4), e835-e842.

Pérez, M., Sefko, J. A., Ksiazek, D., Golla, B., Casey, C., Margenthaler, J. A., … & Jeffe, D. B. (2014). A novel intervention using interactive technology and personal narratives to reduce cancer disparities: African American breast cancer survivor stories. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 8(1), 21-30.

Petraglia, J. (2009). The importance of being authentic: persuasion, narration, and dialogue in health communication and education. Health Communication, 24(2), 176-185.

Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 19, 123-205.

Rufín, R., Medina, C., & Rey, M. (2013). Building trust and commitment to blogs. The Service Industries Journal, 33(9-10), 876-891.

Shrum, L. J. (1996). Psychological processes underlying cultivation effects: Further tests of construct accessibility. Human Communication Research, 22, 482-509.

Shrum, L. J. (2004). The cognitive processes underlying cultivation effects are a function of whether the judgments are on-line or memory-based. Communications, 29(3), 327-344.

Shrum, L. J., & O’Guinn, T. C. (1993). Processes and effects in the construction of social reality: Construct accessibility as an explanatory variable. Communication Research, 20(3), 436-471.

Smith, B., Papathomas, A., Martin Ginis, K. A., & Latimer-Cheung, A. E. (2013). Understanding physical activity in spinal cord injury rehabilitation: Translating and communicating research through stories. Disability & Rehabilitation, 35(24), 2046-2055.

Stewart, C. O. (2013). The influence of news frames and science background on attributions about embryonic and adult stem cell research frames as heuristic/biasing cues. Science Communication, 35(1), 86-114.

Sunstein, C., & Reisch, L. (2013). Automatically green: Behavioral economics and environmental protection. Harvard Environmental Law Review, 38, 127

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124-1131.

Van Laer, T., & De Ruyter, K. (2010). In stories we trust: How narrative apologies provide cover for competitive vulnerability after integrity-violating blog posts. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 27(2), 164-174.

Van Laer, T., de Ruyter, K., Visconti, L. M., & Wetzels, M. (2014). The extended transportation-imagery model: A meta-analysis of the antecedents and consequences of consumers’ narrative transportation. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(5), 797-817.

Volkman, J. E., & Parrott, R. L. (2012). Expressing emotions as evidence in osteoporosis narratives: Effects on message processing and intentions. Human Communication Research, 38(4), 429-458.

Weberling, B. (2012). Framing breast cancer: Building an agenda through online advocacy and fundraising. Public Relations Review, 38(1), 108-115.

Workman, M. (2012). Validation of a biases model in strategic security decision making. Information Management & Computer Security, 20(2), 52-70.

Yang, S. U., Kang, M., & Johnson, P. (2010). Effects of narratives, openness to dialogic communication, and credibility on engagement in crisis communication through organizational blogs. Communication Research, 37(4), 473-497.

Yoo, J. H., Kreuter, M. W., Lai, C., & Fu, Q. (2013). Understanding narrative effects: The role of discrete negative emotions on message processing and attitudes among low-income African American women. Health Communication, 29(5), 494-504.

Zhang, L., & Min, Y. (2013). Effects of entertainment media framing on support for gay rights in China: Mechanisms of attribution and value framing. Asian Journal of Communication, 23(3), 248-267.